ロンドン公演vs.アムステルダム公演 (English)

英語版のイヤホンガイドサービスがスタートした1982年から、イヤホンガイド解説者をさせて頂いておりますロナルド・カヴァイエです。毎月イヤホンガイドのテーマばかりで読者の皆様を退屈させてしまうのは恐縮ですが、今回は、先月お伝えした2006年ロンドン公演に続き、アムステルダム公演での様子を取り上げたいと思います。

十日間にわたったロンドン公演に対して、アムステルダムでは数日間のみの公演となり、イヤホンガイドではなく、劇場の字幕表示装置が使われることになりました。私の本業とは少し異なりますが、歌舞伎の台本が読める者が必要だったため、今回は字幕表示を担当しにアムステルダムへ行って参りました。私もオランダ語は解りませんが、台本を追いながら、台詞の番号のふられたオランダ語字幕を、コンピューターを使って挿入しました。

そこで興味深かったのは、イヤホンガイド付きのロンドン公演と、字幕付きのアムステルダム公演での観客の反応には違いがあったことです。

歌舞伎舞踊は繊細な美の芸術です。複雑な掛け詞がちりばめられた長唄の歌詞は、さまざまな情景を描きます。歌舞伎の音楽と舞踊は(それぞれのもつ意味を理解していれば)、観劇者のすべての感覚を刺激します。

ただし字幕表示には、表示できる文字数が限られてしまうという欠点があります。たとえば『藤娘』のある場面では、

手紙を出したのも無駄だった。-「文も堅田の片便り」

と、表示されました。一方ロンドンでは、ポール・グリフィスによる次の訳と解説が入ります。

(訳)「手紙を出したが返事の便りはなかった。」

(解)「文も堅田の片便り」、の「片便り」は堅田の落雁を連想させます。

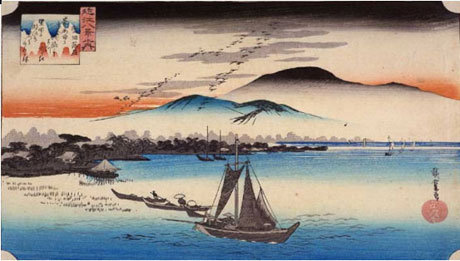

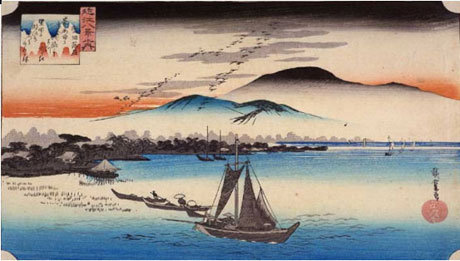

ここの掛け詞は「堅田」という地名と、返事が来ないという意味の「片便り」です。これは歌詞の近江八景に関する解説の八つのコメントのひとつにしか過ぎませんが、このような解説がなくては長唄の意味が失われてしまいます。『藤娘』で描写されている情景は娘の感情描写でもあると同時に、長唄自体の意味も深めています。堅田といえば広重のあの有名な浮世絵作品の『堅田の落雁』です。一日の終わりに雁が列を成して渡る情景は昔から孤独感を表し、想い人を失ってしまった娘の寂しい気持ちを反映しているのです。

安藤広重『堅田の落雁』

ですからアムステルダム公演の観客は、字幕だけでは字幕と舞台との関連が分からなかったのです。対照的に、ロンドンではイヤホンガイドを通じて、歌舞伎舞踊の振りと歌詞の説明も加わり、観客はこのふたつがどのように関わりあっているかも理解できたわけです。『藤娘』を全体的に鑑賞できたことがまた、さらに感動を強くしたようです。

私は自身がコンサートピアニストですから、このような事柄に特に関心があるのかもしれません。西洋音楽であれ歌舞伎舞踊であれ、ただ何かを「美しい」と感じるだけではなく、真の芸術鑑賞とは知識や経験があってこそ、できるものだと思うのです。

そして字幕のもうひとつの問題点は、字幕を読むたびに観客の注意が舞台からそがれてしまうことです。車を運転しながらラジオは聞けますが、テレビを見ながら運転するのはとても危険ですね。(カーナビが原因の交通事故も最近は増えているのでしょうか。)

字幕文字ではなくて役者たちを観に、私たちは劇場へ行っているのではないでしょうか。シェークスピアの舞台を見に行って字幕だけを読んで帰る人はいるでしょうか。来年の三月、パリのオペラ座で市川團十郎さんと市川海老蔵さんが出演される『勧進帳』には字幕がつく予定です。展開が速く見ごたえのある「山伏問答」の舞台を誰も見ていなかった、ということになってしまうのではないかと気になるところです。字幕を読むのに精一杯で、誰も役者さんたちに目を向けずに過ぎてしまうことでしょう。そして解説もないのです。まあ、あったとしても読みきれないでしょう。

外国人にも日本の古典文学が理解できれば理想的ですが、それはやはり無理ですので、歌舞伎鑑賞にはどうしても英語訳と解説が必要になります。完璧ではないけれど絶妙なタイミングで両方が入るイヤホンガイドは、この文化の壁を字幕よりも効率的に埋められるのです。

来月もまた私、ロナルド・カヴァイエからお便り致します。

■ロナルド・カヴァイエ

コンサートピアニストとしてロンドン、ハノーバー、ブダペストで学んだ後、1979~1986年、武蔵野音大にて教鞭をとる。現在はロンドンに住み、年に数回、コンサート、授業、講演などで来日している。

最初に歌舞伎を見たのは1979年。1982年には最初の英語イヤホンガイドの解説者になる。音楽教育と歌舞伎に関する著書があり、1993年に「Kabuki - A Pocket Guide」(Charles E. Tuttle)を日米で、2004年には「A Guide to the Japanese Stage」(講談社インターナショナル)をポール・グリフィス、扇田 昭彦との共著として出版した。

2002年には、鈴ヶ森を「Kabuki Plays on Stage Vol. III - Darkness and Desire」(University of Hawai'i Press)へと翻訳し、昨年は松竹とNHKが制作する歌舞伎DVDの新シリーズの解説、字幕制作をおこなった。

Although I have been an English language Earphone Guide narrator since the service first started in 1982, I don't want to bore my readers by writing about the Earphone Guide every month. However, as last month's letter was about the June, 2006 London performances, I'd like to continue that theme with the story of the performances in Amsterdam which followed immediately after.

The Amsterdam performances were only a few days, compared to the ten days in London, and the theatre wished to use their in-house subtitle system rather then the Earphone Guide. Although it's not my usual job, I went to Holland because somebody who could read the Kabuki script was needed to cue the Dutch subtitles. I don't speak Dutch, by the way, but the subtitles are numbered and, using a computer, I simply had to cue each comment as it occurred in the script. It was very interesting to compare the reactions of the Amsterdam audience (with subtitles) with the London audience (with the Earphone Guide).

Kabuki dance is an art form of great beauty, subtlety and complexity, and the lyrics are often a series of evocative images which contain frequent and extremely sophisticated word play. Dance appeals to all senses - the music we hear, the movements (in particular the mime called furi) which we see, and the text which we should understand. The problem with subtitles is that there is no space to include information other than a translation of the lyrics. During Fuji Musume ("The Wisteria Maiden"), for example, at one point in the dance the audience in Amsterdam saw the following (in Dutch, of course)-

"I have sent letters in vain." - 「文も堅田の片便り」

In London, however, Paul Griffith's Earphone Guide commentary told the audience the following -

"The letters, however, were one-sided, for she received no reply." Here, "one-sided", "katadayori", evokes the sight of descending geese at Katada.

The word-play centres on the place-name Katada and katadayori which means "an unanswered message". This was just one of eight comments which explain the references to the Omi Hakkei, the "Famous Views of Omi" which are cleverly worked into the lyrics. Without understanding these references much of the meaning behind the lyrics is lost. In Fuji Musume each of the views has great emotional resonance that compliments the meaning of the text. Katada, for example, was a view which was associated with alighting geese. There is a famous print of it by Hiroshige -

Hiroshige Ando, the Omi Hakkei, the "Famous Views of Omi"

Geese descending at the end of the day was a scene traditionally associated with loneliness which is especially appropriate here because the maiden is lonely for her lost love.

In Amsterdam, despite having a translation to read, the audience couldn't understand how the lyrics related to what they saw on stage. But in London, both the lyrics and the furi were translated and explained, and the audience was able to understand the relationship between the movements and the text. They could appreciate the dance as a whole and this clearly had a much greater emotional impact. I, as a concert pianist, am particularly concerned about such things. Simply feeling something or admiring it's beauty - whether it be musical beauty or the beauty of a dance - is all right, but a real appreciation only comes with knowledge and experience.

Another major problem with subtitles is that they are distracting. One has to look away from the on-stage action to read them. After all, we can safely drive a car and listen to the radio at the same time. But watching TV and driving is very dangerous. (I wonder how many more accidents there are these days because drivers are trying to read their satellite navigations systems?!) We go to the theatre to see actors perform, not to read a text. No one goes to see Shakespeare and sits there reading the play! Next March Danjuro and Ebizo will perform Kanjincho ("The Subscription Scroll") at the Paris Opera which has already decided to use subtitles. Throughout the yamabushi mondo (interrogation scene) which is extremely fast and very exciting to see, nobody will be watching the stage! Everybody will be so busy reading that the fine performances of the actors will surely go unnoticed! And there will be no explanation (kaisetsu). If explanations are included then, of course, the subtitles will become even longer and the audience will spend even more time reading!

In a perfect world we would all be able to understand classical Japanese. But as most foreigners can't, then a translation and/or explanation is necessary. It may not be perfect but, because it is so sensitively and expertly timed, the Earphone Guide is a much better way of explaining Kabuki than subtitles.

Ronald Cavaye will be sending another letter next month.

Ronald Cavaye

Ronald Cavaye is a concert pianist who studied in London, Hannover and Budapest. He was professor of piano at the Musashino Academy of Music in Tokyo between 1979-1986. Now living in London, he returns to Japan several times a year for concerts, teaching and lectures.

Ronald Cavaye first saw a Kabuki play in 1979 and in 1982 became one of the first narrators (kaisetsusha) of the English Earphone Guide. He has written books on music education and Kabuki - "Kabuki - A Pocket Guide": Charles E. Tuttle, USA and Japan, 1993 and "A Guide to the Japanese Stage": (with Paul Griffith and Akihiko Senda), Kodansha International, Japan, 2004.

He translated Suzugamori for "Kabuki Plays on Stage Vol. III - Darkness and Desire": University of Hawai'i Press, 2002 and for the past year has been working on the commentaries and subtitles of the new series of Kabuki DVDs being produced by Shochiku and NHK.